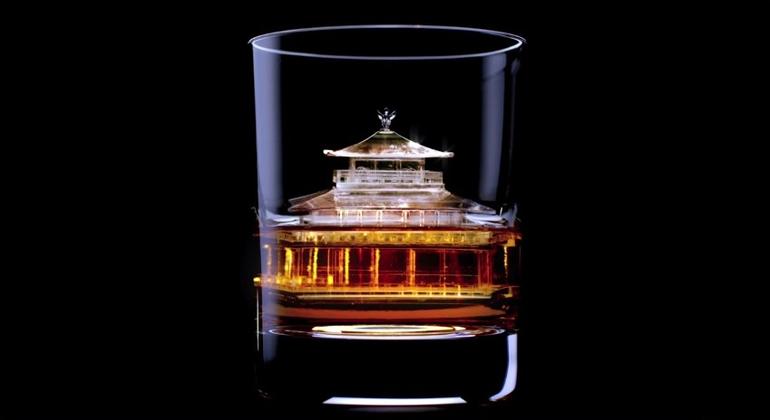

Whisky is not the first drink that pops into the minds of most Westerners when Japan is mentioned. Most people probably imagine the Japanese to be sake-drinking samurais. But the Japanese do in fact make all sorts of drinks, including sake, shochu, wines, beers and whisky.

Beer is the most popular alcoholic drink in Japan and the Japanese are quite good at making it. But whisky is also popular.

The history of Japanese whisky isn’t all that long compared to say, the history of Scottish whisky. Nevertheless, the Japanese have managed to produce some of the best whiskies in the world. Japanese whiskies are known throughout the world for their distinctive taste and high quality. They win award after award, putting competitors to shame. Famed for their mild texture and pleasant aroma, they rival the best whiskies Scotland can offer, and some say Japanese whisky makers even outdo the Scots! How did this nation manage to produce such high quality whisky?

One of the reasons is that the original makers of Japanese whiskies settled for only the best: They modeled their production on Scottish patterns and even went to Scotland to study whisky making in great detail. The results are something no whisky lover should miss out on.

Another reason can probably be found in Japan’s outlook and the way the Japanese work. When modernity came to Japan, the Japanese adopted a strategy to deal with it: Wakon Yosai, or in English “Western technology, Japanese spirit.” It meant that Japan could use the best techniques available in the world and hopefully improve on them while making them fit for Japanese circumstances. Wakon Yosai became a bit like a national motto. It wasn’t just applied to politics, but to trade and production as well. And they certainly managed this with whisky — not only is it one of the best (if not the best) in the world, it is also distinctively tailored to Japanese tastes. And the rest of the world seems to like this taste too.

Today the Japanese make whisky in true Wakon Yosai fashion. They use the best technology imported from the homeland of whisky, Scotland, and add a little bit of their own ingenuity to it. The result is a combination that has been recognized worldwide.

The story

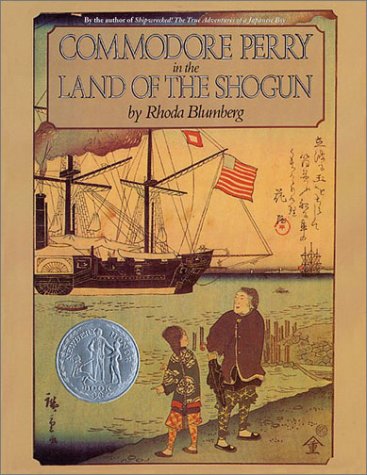

Whisky drinking in Japan is as old as Japanese modernity itself. In 1853, when commodore Matthew Perry sailed his big black ships to Edo harbor, forcing the reluctant samurai rulers to open Japan to trade, he brought with him a few barrels of whisky to keep himself and his crew warm on the long voyage across the Pacific. He also intended to demonstrate American prowess and ingenuity to the Japanese, and what better way to do this than to present the Emperor with the best of what America had to offer? One of the things he presented was a 110-gallon barrel of his finest whisky. There are no stories about what the Japanese court thought about this gift, but presumably they put this strange, amber-coloured, pure-looking beverage to good use.

Only two decades later, the Japanese began importing whisky, and local brewers also started making their own versions. This early “whisky” was actually just alcohol with a similar colour to whisky; it wasn’t very refined, to say the least. The actual history of real Japanese whisky does not start until the mid-1920s when two men — Shinjiro Torii and Masataka Taketsuru — joined forces to found the first authentic whisky distillery in Japan.

Torii was a pharmaceutical wholesaler who had done reasonably well; in his mid-20s, he wanted to expand his businesses and started importing Spanish port wines. Soon after, he created his own brand called Akadama Port Wine which proved a great success. Within years it dominated the Japanese port wine market and made Torii a very rich man. But he wasn’t content. He wanted something more. Torii was a big fan of whisky, a drink which although known in Japan hadn’t really caught on. The import of whisky was minimal, and the only thing the local variety had in common with genuine whisky was, as already mentioned, the name and colour. Torii wanted to change all this. He wanted to make whisky popular in Japan and he wanted to create a true, genuine Japanese whisky, authentic but also suitable for Japanese tastes.

This task wasn’t quite as easy as it may sound. Whisky making is complicated. One has to know what tools to use, how to use them, what the correct ingredients are, how to maintain suitable temperatures and what kind of climate to brew in. Was there anyone in Japan who could do this? At first Torii considered employing a Scottish specialist, but then he learned by a word of mouth of a young man in Japan who had actually spent time in Scotland studying the procedure, a man who shared his zeal for introducing Japanese whisky to Japanese consumers. His name was Masataka Taketsuru.

Masataka Taketsuru had taken classes in organic chemistry at the University of Glasgow and had also worked at a number of Scottish distilleries. He was a whisky lover who wanted to make genuine Japanese whisky, a whisky like Scottish whisky but for Japanese tastes. When the two men met, Torii hired Taketsuru to put up a distillery. Torii had already searched throughout Japan for a suitable location and eventually settled on Yamazaki, near the ancient capital of Kyoto. Taketsuru actually wanted the factory to be built on the northern island of Hokkaido, as its climate was as close to Scottish climate as the Japanese climate could get, but Torii considered the transportation costs to be too expensive.

Yamazaki wasn’t a bad choice as it had been famed for centuries for excellent water; an ancient tea master allegedly had his teahouse there just because of the excellent water the location provided.

It took a few years to produce whisky good enough to meet Torii’s standards. By 1929 he believed he had it when he introduced the Shirofuda whisky. It was so successful that a Japanese newspaper declared that from then on, there would be no need to import whisky anymore as Japanese whisky was good enough by far. Shirofuda was the first authentic Japanese whisky, and it is still sold today.

Taketsura for his part worked a few years for Torii; after that, he decided to found his own whisky distillery in Hokkaido, just as he had always wanted. He named it “Dainipponkaju” — not a very catchy name. Later on he would change the name to Nikka, while Torii would also change the name of his company to Suntory (Torii san backwards). Today Suntory and Nikka are still the largest and most prominent whisky distilleries in Japan. Both have won several international awards. Success came slowly, however, as the first few years were difficult. People still were not used to drinking whisky and the newly founded industry operated at a loss.

This changed quickly when the war came to Japan. The army and especially the navy were mad for the stuff, and from the years 1937–1945 the whisky industry went from a loss of over 50.000 JPY a year (a hefty sum at the time) to a profit of over 100.000 JPY a year. Nikka’s Yoichi distillery even acquired status as a military installation as the army simply could not function without a lot of booze. As a result, both companies survived World War II, and after the war they thrived even more, as there was a new army in town no less thirsty for whisky — the US army. The US kept a large standing army in Japan during the occupation period. British soldiers were also stationed there, and they needed whisky. Both Nikka and Suntory made a fortune, and the domestic whisky market also continued to expand. After the Americans left, the market shrank a little but there was still increasing demand for all sorts of Western-style alcoholic drinks, including beer, wine, vodka, gin and whisky. Fancy bars including whisky bars were established all over Japan to cater to the new army of curious drinkers.

Then came the whisky boom of the 1970s and ’80s. With the Japanese economic miracle, the demand for drinks exploded, and whisky became especially fashionable. By the early ’80s the annual consumption of whisky in Japan was around three litres per person. Sales of imported whisky increased massively, and domestic whisky also became more popular; many sake distilleries were even converted to whisky distilleries in order to meet demand and make a little cash. Most of them did not last. As of today there are nine nationwide whisky distilleries in Japan with many smaller local ones. Although each has its own unique style, most follow the Scottish way of making whisky. Just as in Scotland, the whisky is usually distilled twice with pot stills.

Today Japan is the world’s third largest producer of whiskies after Scotland and the United States. In 2003, Yamazaki 12 year old whisky, distilled by Suntory, won a gold medal at the International Spirits Challenge. The company’s Hibiki 30 year old won that same gold medal the very next year. This was not a lucky strike as Japanese whiskies continue to win prizes at international awards. In fact, Japanese whiskies have won first prize awards at the World Whisky Awards (WWA) every single year since 2007, often in more than one category. And that’s not all. In 2013 Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible declared that Suntory’s Yamazaki Single Malt Sherry Cask 2013 was the best whisky in the world. According to Murray, the whisky has a “nearly indescribable genius.” He gave it a score of 97.5 out of 100. Not bad for a nation that has been making whisky for less than a century!

Because of these accolades, the demand for Japanese whisky is growing again. While the domestic market remains relatively stable, overseas consumers have begun noticing Japanese whisky. Today 5 percent of all whisky consumed worldwide is Japanese and the market can only go up, as the quality of Japanese whisky has been thoroughly established and whisky lovers all over the world are thirsty for a little more. For those who demand only the best, Japanese whiskies are a godsend; their mild taste and steady quality are admired by whisky fans all over the world.

But how do they do it? What ingredients and techniques do the Japanese use to make their whisky so delicious? Well, to begin with they use the best stuff there is. Japanese whisky makers often import barley from Scotland, some peated, some not, and others import from Australia. Oak, bourbon and sherry casks are often imported from Scotland, the US and Spain.

But Japanese whisky wouldn’t be as notable as it is if it didn’t come with a bit of Japanese flavoring. Distillers in Japan have been extremely ingenious in discovering new ways to make their whisky distinctively Japanese. Among other things, they’ve tried new stills with new shapes, many different types of yeast, malts and barley, new mixing techniques, and all sorts of different casks. Some whiskies are allowed to mature in native Japanese oak. Distillers also carefully select the location for brewing using only the highest quality water.

Lastly, Japanese climate in general (except on the northern island of Hokkaido) is far warmer and more humid than in Scotland. The winters can be cold while the summers are hot, and this extreme difference in temperature affects the whisky while it is maturing.

All this combined makes Japanese whisky what it is today: a world-class alcoholic beverage that whisky lovers around the world rave about. If you haven’t tried Japanese whisky yet, trust us, you are missing out!

Published: May 26, 2015Author: Henry Baldvin