Clay Risen is the deputy op-ed editor at The New York Times, and author of Single Malt: A Guide to the Whiskies of Scotland and the spirits bestseller American Whiskey, Bourbon & Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. Over the years, his meticulous research, excellent books and expert knowledge have led to him being widely regarded as one of America’s best spirits writers.

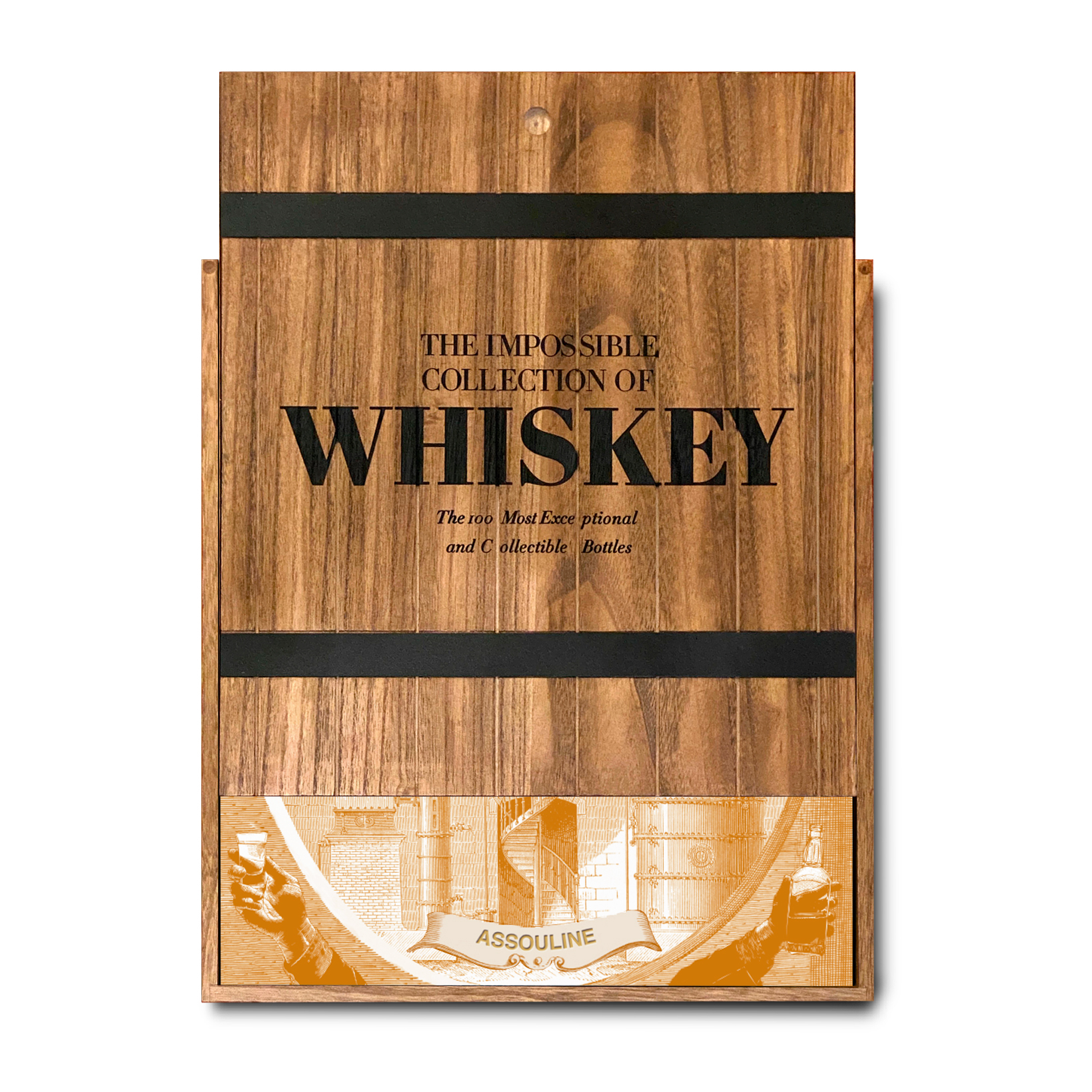

This week, I was lucky enough to have the chance to interview Risen about his exciting new book, “The Impossible Collection Of Whiskey: The 100 Most Exceptional And Collectible Bottles”. He touched on the premise, his criteria for selecting bottles, the difficulties with narrowing it down to just one hundred, a couple of truly fascinating expressions and much more.

Here’s what he had to say.

Your new book “The Impossible Collection Of Whiskey: The 100 Most Exceptional And Collectible Bottles” launches soon. Can you tell me a bit about the premise of the book, and your inspiration?

The book is part of a series on luxury collectibles assembled by Assouline – previous entries include wine, cigars, things like that. The premise is, literally, what is your “impossible” list? If you could ignore price and availability, what are the 100 bottles you would have in your collection? What I found intriguing about the premise was that it didn’t come with criteria – these aren’t necessarily the 100 most expensive, or the 100 rarest, or even the 100 most legendary bottles, though price, availability and reputation were all part of my calculation. I had significant leeway to include bottles that I think are important for historical reasons, for sentimental reasons. Ultimately, my core criterion was that each bottle had to tell a story. For instance, there’s a bottle of 28-year-old whiskey from the Czech Republic, distilled when it was still communist Czechoslovakia – almost regardless of how it tastes, that is amazing to me, and well worth including (though it happens to taste phenomenal).

What piqued your interest in collectible whisky?

Let’s set aside the obvious – that I love whiskey, and want as much as I can find. I collect whiskey because, for one, I love to share the things I value, and whiskey is a wonderful thing to share. It is more or less shelf stable, unlike wine, so you can have multiple bottles open in your cabinet that you can bring out when friends come over. So in that sense all whiskey is “collectible.” The whiskeys I look for, that I collect, are whiskeys that tell a story – it can be a story about their production, about the distillery, about whiskey history, or it can be a personal story, something about the whiskey that allows me to say something about myself. I collect Blanton’s not only because it is a wonderful whiskey and historically significant as the first single-barrel bourbon, but also because my grandfather introduced it to me.

What was your barometer for “Exceptional and Collectible Bottles”?

Obviously, these couldn’t be everyday bottles. So while each bottle had to have a story to tell, they had to clear a minimum bar regarding availability (or lack thereof) and reputation. Price wasn’t a criterion, but it more or less followed – if you have a rare bottle everyone wants, it’s going to be expensive. After all that, I also wanted to make sure the list was representative of whiskey today. I could have easily picked 100 bottles of Scotch and called it a day. But I wanted my list to include world-class whiskeys from outside Scotland and the US – not just the obvious, like Canada, Japan or Ireland, but the emergent, and more obscure, like Australia and India.

What was your process in selecting the featured bottles?

I started by brainstorming my own list, which got me to well over 100 bottles. Then I spent some time looking at auction sites and review sites like Whiskybase.com, both for bottles I may have missed as well as for insights into how to start pruning that list. It was pretty easy to think of 50 bottles, and almost just as easy to come up with 150. The hard part was cutting that down to 100 bottles, and it got harder the closer I got to my target. Those last 110 were a real challenge, and I just know that when people inevitably quibble with my choices, they’ll probably bring up whiskeys that happened to fall out in those last few rounds of cuts.

Given the book features expressions from around the world, did you travel extensively to research? Or were you able to do it from home?

Fortunately no. I’ve certainly done my share of whiskey traveling, and then some. So I didn’t feel it was necessary. Plus this is really a book about the bottles, not the distilleries. And I’m lucky to be in New York, where at least some of these bottles were available at local bars and lounges.

What challenges were thrown up along the way?

One of the big challenges was doing the research on the bottles. Whiskey history can be pretty spotty and unreliable, especially when it comes to older bottlings. So getting enough accurate information to explain why a particular bottle was significant could be a challenge at times – though, I should add, a fun one.

Is there a whisk(e)y that really stood out to you in terms of its story?

One whiskey I included that might surprise some collectors is the centennial edition of Elmer T. Lee, a bourbon produced by Buffalo Trace. It’s a great whiskey, but the bottle’s significance, for me, is historical. Lee was the longtime manager and master distiller at Buffalo Trace, mostly back when it was known as the Stagg Distillery. He is considered one of the greatest whiskey makers in American history; in the 1980s he invented single-barrel bourbon, which jumpstarted the bourbon renaissance in America. More importantly, he and a few others like him – Booker Noe at Beam, Parker Beam at Heaven Hill, Jim Rutledge at Four Roses – held the Kentucky distilling industry together during its darkest times. Without them, their distilleries, and the traditions of American whiskey making, might have collapsed. There is a regular-release expression named for Lee, and in 2019, on what would have been his 100th birthday, Buffalo Trace rolled out a centennial edition in his honor. Is it as good as, say, Black Bowmore? No, but that’s not the point. To me, that bottle tells such an important story, which is why it’s in the book.

Were there any whiskies of note that were on your radar but didn’t quite make the final cut?

Yes! I was very tempted to include Loch Dhu, a 10 year old single malt Scotch made at the Mannochmore Distillery in the late 1990s and widely considered the worst whisky ever. It was reportedly aged in double-charred casks and dosed with a heavy amount of caramel. I’ve had a taste, and it is truly gnarly – a 100-car pileup of rotting fruit, rancid grain and treacly sweet notes. Only a small number of bottles were produced, and not surprisingly, it has developed something of a cult following. I would love to have my own bottle. But I couldn’t quite bring myself to include it in the book.

You’ve obviously studied the whisky landscape quite extensively, with your book including expressions from countries all around the world. Are there any relatively new or unknown markets that you would say are worth keeping an eye on for collectible bottles?

One of the exciting things about the current whiskey boom is that it is global; I’m no longer surprised to learn that, say, Mexico has a burgeoning whiskey scene, and a good one at that. Distillers in Taiwan, India and Australia have already demonstrated an ability to produce world-class expressions, and I expect them to move into the whiskey establishment, alongside Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Japan and the US, in the coming decades. The same will happen with several European countries, top of the list being France, Germany and Sweden, but also Spain, Austria, and the Netherlands. And don’t count out China, which just opened its first whiskey distillery.

What do you think the future holds for exceptional and collectible whiskey?

I’d make a few points. One, I think collectible American whiskey will go global. Right now there’s a big divide between what American whiskey collectors are excited about and what the rest of the world is looking for. Americans geek out over A.H. Hirsch 16 year old, which I doubt many global collectors have ever heard of. The divide is partly because it’s much harder to sell whiskey second-hand, so you don’t have sites akin to Scotch Whisky Auctions to raise the profile of luxury American bottles. But the sheer force of America’s whiskey boom will change that, and sooner than later.

Two, we’re going to see a lot more interest in whiskeys made outside the US and Scotland, as distilleries in “new” countries start to up their game. Kavalan, from Taiwan, is already getting there; distilleries in India and Australia aren’t far behind.

And three, luxury bottles will continue to break records at auction, and as they do, the entire collectible scene will start to change, as more people realize there is a lot of money to be made in it. I’m not sure that’s for the good. Whiskey should be consumed, and shared, but obviously once you open a bottle, it loses much of its value to collectors. I hate the idea of these amazing bottles sitting in a collector’s vault, never to be opened. That’s a point that I hit on over and over in my book. I hope at least some people take it to heart.

“The Impossible Collection Of Whiskey: The 100 Most Exceptional And Collectible Bottles” was published by Assouline and is available in Assouline stores and on www.assouline.com

Feature Image Credit: Assouline

Published: October 13, 2020Author: Liam Hiller